Hundreds of millions of Africans face two problems holding them back from progress: 600 million lack electricity, while virtually all 1.4 billion people on the continent lack high-quality currency. Compare this to the US, Northern Europe, or Japan, where nearly everyone has access to consistent, affordable power and a widely-accepted reserve currency like the dollar, euro, or yen.

The longer that Africans suffer from power blackouts and high inflation, the harder it is for them to get a leg up, despite their best efforts. Worse still, legacy energy and financial providers have no incentive to alleviate this issue, meaning currency debasement, debt traps, and grid shutdowns persist.

Most might look at this scenario and conclude that the next African century will be very difficult. Despite being blessed by abundant energy sources like mighty rivers, blazing sun, strong winds, and geothermal heat, Africa remains largely unable to harness these natural resources for its economic growth. A river might run through it, but human development in the region has been painfully reliant on charity or expensive foreign borrowing. Until now.

In the eyes of some of the continent’s entrepreneurs, educators, and activists, something has emerged that has the potential to revolutionize access to reliable electricity and high-quality currency -- the building blocks of progress -- for Africa’s swiftly rising population. Believe it or not, that thing is Bitcoin.

I. Mining in the Shadow of Mt. Mulanje

A little over an hour southeast of the city of Blantyre, in southern Malawi, along scenic dirt roads, towers Mount Mulanje. A stunning 3,000-meter massif — one of the highest peaks in southern Africa — its complex of cliffs and valleys straddles the border with Mozambique. The jaw-dropping scenery rivals Yosemite, but given its remote location, there are many days of the year where local guides say there are no hikers at all. In any other country, Mulanje might be the site of a top-5 national park — with world-class, soaring granite faces and the biggest vertical climbs in Africa — but most days, the area sits quiet.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the region was hit hard by European and Arab slavery. Portugal, Oman, Britain, and other empires extracted hundreds of thousands of slaves from Mozambique, Malawi, and the surrounding areas to ship off to forced labor in the Americas and the Middle East through regional ports like Zanzibar. At best, 1 in 5 survived the journey. Slave routes passed right through Mt. Mulanje, which was an easily-identifiable marker along the way. Today, the mountain’s foothills are peppered with lush forests, encroaching tea plantations, and farmers growing pineapple, banana, and maize. The ecosystem is a world treasure, with endemic plants and animals including prehistoric cycads, the endangered national tree of Malawi, the Mulanje cedar, and some of the rarest insects and reptiles on earth.

Sadly, the exploitation from long ago continues, just in different forms. Logging and mining threaten the local environment, and without industrial infrastructure, residents are isolated and left to fend for themselves.

The population here may be gifted with many natural resources, but the mother of modern progress has eluded them. Only about 15% of Malawians — and only about 5% of people living in the country’s rural areas — have access to electricity. In Bondo, a small village in the foothills of Mt. Mulanje, some residents got their very first access to lights at night in 2016. “Before then,” according to the town’s senior chief, “there was only darkness.”

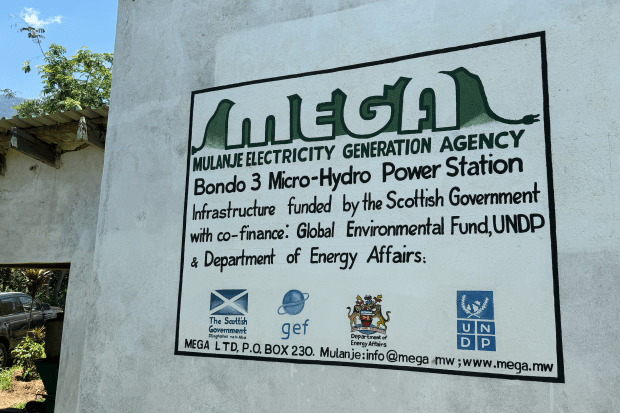

This lack of power creates several problems for a growing population. Instead of flipping on a stove, residents log the area around the mountain, cutting down trees and brush to make fires or to create charcoal for cooking. At night, children study under the light of dangerous paraffin lamps, or don’t study at all. The logging devastates the forest and the fires and lamps create noxious indoor air pollution. Foreign donors — including the Scottish Government — paid for a small hydroelectric plant for Bondo in 2008, and after eight long years of construction, it began to provide power for some of the local population.

During that time, Carl Bruessow — an avid hiker and the head of the Mt. Mulanje Conservation Trust — helped start the Mulanje Electricity Generation Agency (Mega), Malawi’s first privately-owned micro-hydro energy provider. Mega is also a social enterprise with the mission of providing the citizens of Bondo with electricity. The raw cost of power from a small hydro scheme like the one financed by the Scots on the banks of a river on Mulanje is extremely high, nearing 90 cents per kilowatt-hour. For context, residential power in the US or Europe ranges from 10 cents to 20 cents per KwH. Grid power in Africa typically ranges from 20 cents to 40 cents per KwH. For example, in Kenya, it’s 27 cents. Carl, in his efforts to give back to the local community, heavily subsidized this cost for the residents of Bondo. Due to his generosity, they paid less than 20 cents per KwH to Mega for electricity.

Carl covered the difference, but such an operation was not sustainable. Over 2,000 households had so far been connected to the Mega grid, but another 3,000 were still waiting for hookups to their homes, and Carl was running out of money. The power stations were producing more than enough power for 5,000 homes, but much of the electricity was orphaned and unable to be sold, as Mega did not have capital to be able to purchase the equipment to connect new households. There was no capital, either, to consider expansion so that the hydropower would not dwindle in the late summer during the dry season.

In some places, industrial operations might buy orphaned rural power. But in a place like Bondo, there simply aren’t very many power-hungry businesses. The excess electricity couldn’t be sold, so the power stations built machines that existed solely to suck up the unused power. This was especially tragic when there was a lot of rain, or at times of low demand like at night, when the stations were forced to dissipate the overwhelming majority of their precious electricity: a total waste.

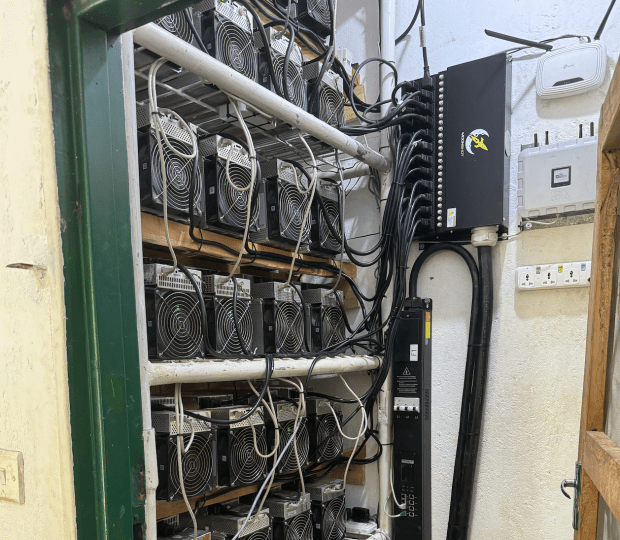

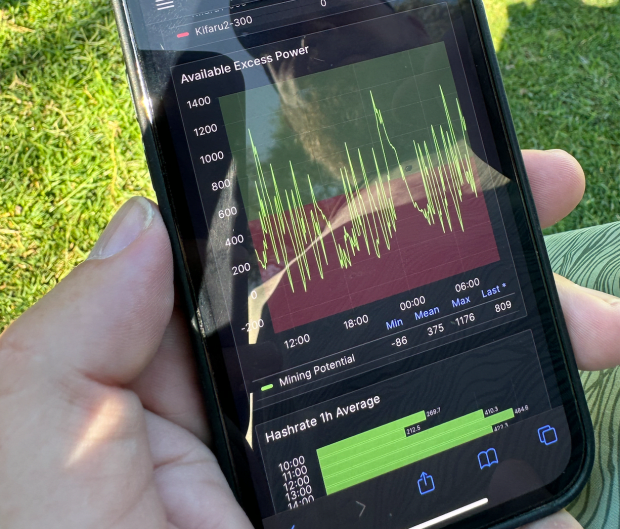

Two years ago, entrepreneurs Erik Hersman, Janet Maingi, and Philip Walton launched Gridless, a new company focusing on off-grid Bitcoin mining in Africa. The trio had backgrounds with companies like Ushahidi, BRCK, and iHub, with expertise in building hardware, writing software, as well as scaling communications and internet infrastructure, giving them a fitting resume for the task. One of their first site visits was in Bondo, where they visited with Carl and inspected Bondo’s power stations. In early 2023, a Gridless Bitcoin datacenter was installed and launched, and now, Carl and Mega have a new source of capital. In December, I was able to travel to Bondo to figure out how it all works.

Today, any and all excess power generated by Bondo’s power stations gets sold in real-time to the Bitcoin network by Gridless’s miners, and Carl earns 30% of that revenue. It arrives directly to Mega’s wallet, in BTC. The new capital is enabling Mega to connect more customers to power, drive costs down, and expand their operations, to eventually connect everyone in the Bondo region to electricity. Mega, the community, and Gridless all benefit. And the most profound part? No aid or government subsidy is required.

Bitcoin is often framed by critics as a waste of energy. But in Bondo, like in so many other places around the world, it becomes blazingly clear that if you aren’t mining Bitcoin, you are wasting energy. What was once a pitfall is now an opportunity. Bitcoin miners can be thought of as dung beetles, scraping up the waste energy that no one else wants and transforming it into something valuable.

As Mega hooks up more and more customers, Gridless may unplug some of their mining machines, and move elsewhere, or perhaps move to harness the output of new power generation stations in the same area that are waiting to connect to their clients. If the Bitcoin network pays X, customers will need to pay X+1, so eventually miners will start to get priced out. But even in a situation where at 5:00pm the local demand from Bondo eats close to full capacity of what’s available, mining can still be lucrative, because there’s so little demand overnight, and the river never sleeps.

Elsewhere in Malawi, the national grid is broken. As of December 2023, people who receive grid power suffer from 6-8 hours of “load shedding” per day, where huge swaths of the country’s population are cut off from power by the electricity company. But in Bondo, there is no load shedding. The mini-grid is properly balanced by the Bitcoin miners. If there’s not enough water power, Gridless’s automated software turns the ASICs off. If there’s too much water power from, for example, one of the tropical cyclones that periodically hammers the region, Gridless’s ASIC operation eats it up. It’s a small wonder that in little Bondo, the electricity works more consistently than in the big cities.

One night during my visit to Bondo, Carl asked me to pause as the sunset was fading, to look at the hills around us: the lights were all turning on, all across the foothills of Mt. Mulanje. It was a powerful sight to see, and staggering to think that Bitcoin is helping to make it happen as it converts wasted energy into human progress.

The potential for this model to scale is mind-boggling. Consider: power generation in Africa is typically planned looking forward, for example, on a 30-year window. So sites are built to provide future capacity, not the capacity of today. So when a site like the one in Bondo boots up, it takes a while before it can get from 0% to even 20% capacity. At that point, before Bitcoin, the power company might have had to charge 5 times the price for the electricity it sold, just to make itself whole.

This is catastrophic for customers, especially those like the ones in Bondo who have some of the smallest disposable incomes on the continent. But with Bitcoin, the network now buys 100% of the all available excess electricity, bringing costs down even if only a small percentage of the power station’s capacity is being purchased by residential or industrial consumers.

We are told to believe that progress is always happening and that pure human innovation is going to make things better and cheaper. But in Malawi, given the collapse of the local kwacha currency, and the lack of incentives for infrastructure investment, the expansion of the electricity grid has not just been stalled, it has been made prohibitive.

Bitcoin fixes this in two ways: by directly delivering a high-quality, peer-to-peer currency to the power generators, and by allowing them to use all of their capacity, all of the time, lowering prices for their customers and raising their profits.

Roughly 95% of all small power generation in rural Africa, according to Erik, is funded with concessional financing, whereas it could take five to seven years to raise funds from charity. The process is dependent on altruism and the subsidy is someone else “doing the right thing.”

The micro-hydro stations in Bondo, for example, were paid for by foreign donors, who can be very helpful for getting a project off the ground but who typically don’t pick up the bill for ongoing operation costs or expansion. They also don’t have very much skin in the game, and are OK with an eight-year timeframe for getting people online. With Bitcoin, the incentives are different. Out with the donors, in with co-investors, who are very interested in getting the power up and running as soon as possible.

Moving forward, there’s much work to do in Bondo. Carl and Mega are currently determining how to leverage their new income stream from the Bitcoin network to connect up hundreds of new homes to electricity. They are also considering an expansion to a new, larger power station to address the issue of lower power output in the two driest months of the year.

It would, of course, be built in partnership with Gridless, so that it could start generating revenue immediately, on day one, even if it takes time to connect new homes and businesses.

The critical importance of electricity was underlined when we met Bondo’s community leaders and members of the residents’ electricity committee. They listed all of the new benefits that the town now receives: they used to have to walk 20 kilometers for things like corn mills, or televisions, or refrigeration, or to charge phones, or for their kids to study at night, or for healthcare, and now they don’t.

The ladies in our meeting even pointed out a funny thing: before, the men of the village would go to town to watch football at night, leaving their families behind. But today, they don’t leave, they just watch it at home and are there for their wives and children. LEDs replace kerosene lamps, reducing fire risk and deadly indoor air pollution. The percentage of children that go on to higher levels of schooling has increased, dramatically. The list of life upgrades goes on and on.

By this point you might be saying, fine, this sounds good, but why not do something else with the electricity generated by Bondo’s rivers? Philip explains that no other business would run better in a place like this, blessed by cheap energy but isolated from infrastructure.

The cost of AI farming, for example, is only in a small way dictated by electricity: a chip might cost $30,000 and use 1200 watts. Contrast this to Bitcoin mining, where electricity makes up a huge portion of cost, and a chip might cost $1,200 and use 3500 watts. So it makes no economic sense to build an AI data center in Bondo, not to mention the connectivity, bandwidth, and latency issues.

Moreover, AI processes cannot be simply turned on and off like Bitcoin mining without causing some kind of harm to the service itself, so AI compute, in its current form, cannot be a grid balancer. But Bitcoin can: when the microgrid needs to deploy electricity elsewhere, miners can turn off easily. Finally, even if Mega tried to service AI companies in Bondo, how would they get paid? It would be the same trap of foreign exchange problems, fees, and dealing with the collapsing local currency. With Bitcoin, they get paid in globally-accepted, 24/7 saleable satoshis.

One more area of potential is the externality of Bitcoin mining: heat. When we put our hands over the air exhaust coming out of the back of the Gridless facility in Bondo, we felt a searing blast. The more miners, the more heat. A miner is in essence a space heater, and a surprisingly efficient one at that.

A new Reason documentary helps explain this, focusing on a bathhouse in Brooklyn, where the owner is now paying less every month in electricity bills to heat his spa water with ASICs than he did using more traditional heating equipment. Any heating operation that is not mining Bitcoin is probably wasting energy.

1,000 miles to the north of Bondo, in the D.R. Congo’s spectacular Virunga National Park, rangers have been mining Bitcoin with stranded hydropower for the past three years, generating critical income for the bioreserve and the five million people who live nearby.

This coming March, the heat from Virunga’s miners will be harnessed to dry cocoa beans. Traditionally, this is done by laying out the beans to roast under the sun, where they are vulnerable to the weather, and to being eaten or stolen by animals. Drying the beans with the hot blast from the miners will dramatically expedite the process, and for minimal additional cost.

Instead of spending $200,000 on an industrial drying operation, the park rangers simply bought $200,000 worth of ASICs that can process cocoa and earn Bitcoin. Moving forward, if any of their competitors process cocoa and don’t mine Bitcoin, they will be wasting energy, and they will be less competitive.

According to environmentalist and Bitcoin advocate Troy Cross, in the last Bitcoin price cycle that crescendoed in late 2021, mining was driven by access to cheap capital, not cheap power. For example: Wall Street borrowing cheaply to buy shares in Bitcoin mining companies.

But in the next cycle, he says, it will be driven by access to cheap power. And this could tilt in Africa’s favor. There might even be places, he says, where the cost to mine, let’s say in Blantyre, exceeds the mining benefit, but the business savings from the excess heat (selling chocolate) makes the whole thing profitable. Really, he says, one should think in terms of: profit from mining plus profit from heat minus the cost of mining. Anywhere where one finds low grade electrical heat, there are unrealized Bitcoin profits.

In Bondo, Mega’s original idea was to make dried pineapple snacks using the excess heat. But on our visit, a new idea was hatched: the mine itself is on a tea plantation. Tea, once picked, needs to be dried within a matter of hours, and it is done so with heaters, which suck up electricity. Why not use ASICs to dry the tea? The operators are now thinking about it.

In a place where electricity is typically exceedingly scarce, it’s a luxury to think about and consider what to do with extra power, but it’s happening in Bondo now that there’s a technology that allows people to harness value that was once just blown out the window.

II. The Collapse of the Kwacha

One Wednesday morning in November 2023, the 20 million citizens of Malawi woke up to find their currency devalued by 44%. The government and IMF argued that the move would boost exports and stabilize the economy, but for the average person, all they felt was an immediate decrease in purchasing power. Many merchants simply closed for the day, as employees needed time to recreate the price labels used everywhere from gas stations to grocery stores.

This was not, like in Argentina, something that most people could escape. In Argentina, there is a widely accessible and sophisticated black market for dollars. In Malawi, this doesn’t exist. People are stuck in the kwacha. According to the country’s Reserve Bank, 85% of Malawians are unbanked, meaning nearly everyone uses paper kwacha notes issued by the government as their main store of value and medium of exchange. Devaluation here remains an effective way to steal from the population.

If one were to design the perfect weapon, something that could hurt everyone in a country at the same time, it’s hard to think of a better one than currency devaluation. Unlike a nuclear blast or bioweapon, it can hurt every single person simultaneously. In this case, the damage was an immediate 44% reduction in the purchasing power and standard of living for millions of people in Malawi, especially the poorer and middle classes who cannot easily access dollars.

It is not as if the government held a referendum, asking the public to vote on whether they wanted their purchasing power to collapse the following week: of course, no one would agree. Devaluation has to be planned and orchestrated mostly in secret, and it tends to be overnight phenomena. So despite the status of Malawi as a partly free country, with relatively free and fair elections, the devaluation was entirely undemocratic. This is part of a larger global issue where financial repression is ignored, even though political repression is discussed and highlighted.

Devaluations, for example, tend to be relegated to the back page of the newspaper, cast as a procedural matter. But they inflict grievous harm. It is a wonder why devaluation is not considered a crime, or even a crime against humanity. The people of Malawi did resist, in a series of protests. These small uprisings were put down, often brutally, by police. And ultimately, the marchers were forced to give up and accept the theft. This wasn’t the first time that the public was robbed of its labor and wages at scale, either: over the past 20 years, the kwacha has lost 95% of its value against the dollar, much of it in planned devaluations like this one.

As we drove through the markets and farms near Blantyre, it was clear that the hard-working people around us did not need such a devaluation. They were already some of the poorest in the world. Malawi’s per capita income, according to the United Nations, hovers around $650 per year. That’s 33 cents per hour, assuming a nine-to-five, five-day work week. And that is, of course, the median rate. For people living in remote areas, it’s probably much closer to $100 per year or 5 cents per hour. And now, each hour of their effort only gets them 56% as much grain, fruit, meat, airtime, electricity, medicine, private schooling, or petrol as it did two months ago.

This particular devaluation, like so many others, was a result of foreign pressure from the IMF and World Bank, who want client countries to pass through austerity before receiving any fresh new funds. Austerity is a euphemism for weakening the currency, ending subsidies on basic goods, shrinking welfare, raising taxes, crushing unions, harming small local businesses, and creating more favorable conditions for large multinational corporations and buyers of any locally harvested, excavated, or produced goods.

After completing the late 2023 devaluation and pleasing its creditors, Malawi received the green light for a $137 million World Bank loan, as well as a new loan of $175 million from the IMF. $115 million of these loans have already been paid out as of early December: a Christmas bailout for the country’s corrupt bureaucrats. The IMF projects that Malawi will need $1 billion in debt relief over the next three years, ensuring that a lot more currency devaluation is on the horizon.

Word on the street is that another devaluation, perhaps another 25%, is coming.

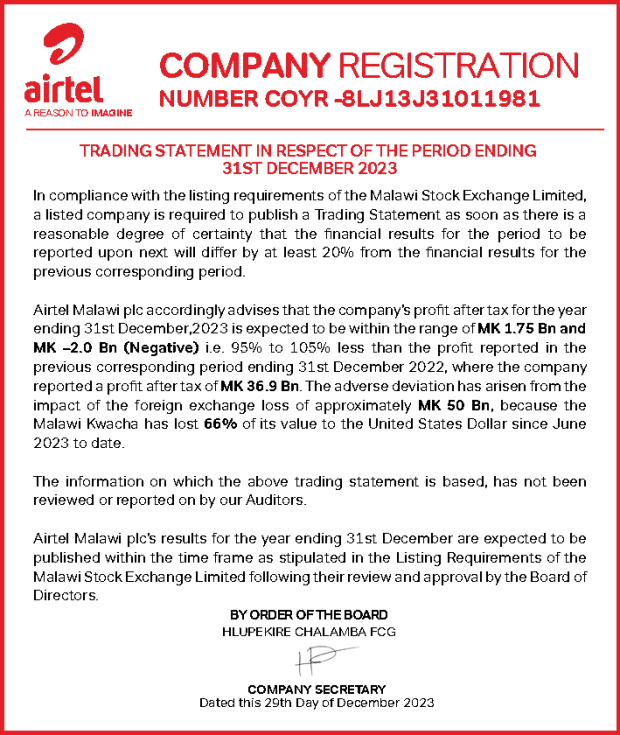

The macro impact on the country’s economy has already been huge: Airtel, one of the country’s largest mobile operators, posted a statement at the end of 2023 that the company’s profit is expected to be 100% less than the profit posted in 2022. “The adverse deviation,” they write, “has arisen from the impact of the foreign exchange loss… because the Malawi Kwacha has lost 66% of its value to the United States Dollar since June 2023 to date.” Citizens might have stopped protesting in the streets against this disaster, but some are finding other, more quiet ways to wage a revolution.

Grant Gombwa is a student living in the Blantyre region, and is one of the country’s first Bitcoin meetup organizers. He loves the idea of a currency that no government can devalue. Malawi’s first official Bitcoin meetup will take place in February in the capital, Lilongwe. Grant will make the 5-hour drive to unite with perhaps two dozen other Bitcoiners. It’s a modest start, but given the economic conditions, it’s likely a trickle in what will eventually become a flood of new Bitcoin users. Grant said that, personally, what inspires him is that before he was stuck, unable to pay for anything abroad with his native currency. But today he has an upgrade, and can speak the same monetary language as someone in New York, Cairo, or Beijing.

Grant estimated that among young people in Malawi, between 18 and 30 years old, that nearly all of them owned a phone, and that around two-thirds owned smartphones. Not all smartphone users can afford consistent data, of course, but that doesn’t prevent them from using Bitcoin.

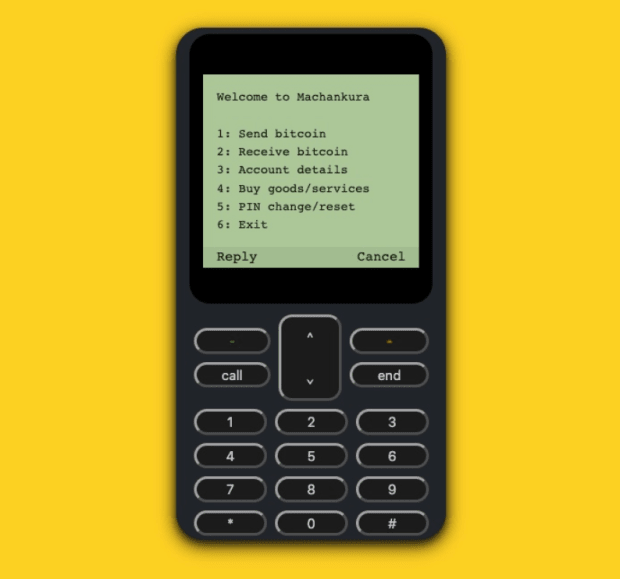

As we’ll learn more about later in this story, Africans in countries like Malawi can use a service called Machankura to send or receive Bitcoin from any feature phone, or any smartphone with no data: no internet required. This means that an economic escape route is here – it just will take Grant and other local educators some time to show people the way.

In one of our conversations, Grant explained a potentially promising idea. The Malawian government, he said, with incentives from foreign lenders, is installing electric vehicle charging stations across the country. He guesses that very few locals will actually be able to afford these types of cars, especially in the first few years. So these solar-powered electric generators will be for the most part sitting, unused, wasting the sun’s energy. Enter Bitcoin.

Grant’s idea is to bring a few ASICs to these likely-idle charge-points, hook them up, earn some satoshis, and pay a percentage to the owner of the property to make sure he doesn’t get kicked out. We’ll see if Grant’s idea gets traction. But what’s certain is that there will be many more ideas like it, springing out of places like Blantyre and Bondo now that wasted energy can be turned into capital.

III. Turning Fire into Digital Gold

The Great Rift Valley is one of the largest areas of seismic and volcanic activity on earth. The geothermal energy potential in this part of Africa, stretching 7,000 kilometers south from the Red Sea to Mozambique, is vast and nearly entirely untapped.

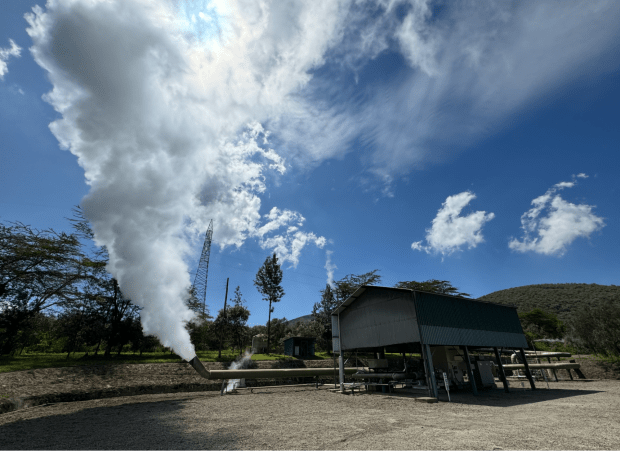

To get a sense of the potential that Bitcoin mining could have on the region, I visited a site a few hours outside of Nairobi, Kenya, on the shores of Lake Naivasha. The situation is representative of any number of industrial operations in rural Africa, or for that matter, in rural places anywhere in the world. A 1.4 megawatt geothermal plant (which funnels hot steam rising out of a 2,000 meter-deep hole through a turbine to generate electricity) powers a water pump perhaps a kilometer away on the shores of the lake.

The pump pushes the lakewater up to a nearby complex of fields, where flowers are grown and exported to supermarkets in Europe. This is just one such flower farm in a country full of them: Kenya is the world’s largest flower exporter, and all of those fields need irrigation, and all of that irrigation needs power.

Here’s the thing: these water pumps do not consume power in a consistent way. But geothermal power is always on, hinting at a tremendous amount of electricity waste just waiting for someone (or something) to come and buy it up. Geothermal is probably the single best existing power source in the world for Bitcoin mining. Hydro is great, but during dry months, it can slow down. Nuclear might be better in a vacuum, but it’s impractical at the moment for small sites, and at least a decade away from a rollout across Africa.

Geothermal is 100% clean and 100% consistent. A plant like the one here in Naivasha could run for 40 years, with no interruptions, and no change in power output. It’s one of many that make up a total of 1 gigawatts (i.e. one thousand megawatts) of power generation just in this region alone. The foreman in charge of the site tells us that the surrounding hills and valleys could actually support up to 10GW of geothermal electricity, but the rest remains untapped.

Down at the pump, we see something that could soon be present at any industrial operation in the African countryside: a small shack, with a Starlink on top emitting a strong hum. Inside are 144 Whatsminer ASICs, set up, neatly corded, and run by Gridless. Everything from the hut itself to the software is custom-made in Africa by Africans. It’s a 500-kilowatt operation, which is about perfect, according to Erik, for a situation like this. He shows me the actual electricity used by the ASICs on his cellphone: about 375KW on average, every day. This is projectable into the future. Gridless has done a 5-year backstudy on Bitcoin mining revenue, and can predict being paid between 7 and 9 cents per kilowatt hour by the Bitcoin network. If the BTC price goes up, the earnings get beaten back down by the new mining competition. If the BTC price goes down, it becomes easier to mine: the difficulty adjustment in action.

The upfront cost for a set-up like the one on Lake Naivasha runs in the low six-figures including the ASICs and other infrastructure. Daily revenue for the Bitcoin mine will be a few hundred dollars. Gridless pays out 30% of the revenue to the power company as a flat fee for the right to use the stranded electricity. Depending on the consistency of the excess energy, Gridless generally recovers their investment within a few years.

One can quickly see how Bitcoin mining is going to be enormously profitable across Africa. “If you know you are building a variable-demand power station in the future, you will incorporate Bitcoin mining from the start,” says Erik. “Otherwise, you are wasting energy.”

Storing the energy in batteries and using it later sounds like a nice idea, but doesn’t make economic or technological sense right now, he says. Imagine a slightly larger 2-megawatt operation similar to the one at Lake Naivasha, that could be $1,000,000 in gross revenue per year, and not in kwacha or shillings, but in cold hard satoshis, payable directly to the site, no accounting office or foreign exchange costs required.

The scene by the lake is perfectly solarpunk: the earth’s heat is powering agriculture, and the Bitcoin mine is eliminating any electricity waste, and converting it instead into digital gold. It’s sitting here in a place like this that you realize that not Bitcoin mining is such a staggering waste of energy.

Later, as I talk with the Gridless team about the implications of the Lake Naivasha site at a restaurant in Nairobi, the power goes out during our meal. Janet tells me that this is typical in Kenya but that Bitcoin can help fix this, as a demand response technology.

“During the day, there’s a lot of demand, and we turn off our machines,” she says, “At night, when people go to sleep, we turn on our machines. Normally, if there’s too much unplugging too fast, it can cause blackouts. But we can balance the grid with more Bitcoin mining. We can absorb sudden incoming power, and we can slow sudden collapses of power by turning off.”

ASICs can be turned on and off at a moment’s notice without harm to the operator, unlike manufacturing or other compute processes, making Bitcoin mining one of the best technologies in the world for stabilizing grids.

What Gridless is doing at small scale with offgrid energy could also help the national grids struggling all across the continent.

Micro-hydro and geothermal aren’t the only power sources that Gridless is tracking. Solar, they say, only provides energy during one third of the day, and requires expensive battery technology to be viable. Such batteries could triple the cost of operating a power site, making it far less appealing.

Gridless does have its eye on a few wind sites, but another option is biomass energy. In the past weeks, the company has brought two new East African Bitcoin mining sites online, powered by biomass.

One new mine adorns a sugar processing facility, and one complements a plant that refines sisal, a tough fiber used for rugs, rope, and other textiles. In both cases, the leftover plant material is burned and the heat boils water to power a turbine, generating electricity. In both cases, as is the case for most African industrial operations, the site is too far from any residential communities to directly power homes or other businesses. Often, the electricity is simply just run straight back into the ground.

Biomass is generally considered clean and renewable: sisal and sugar plants suck carbon dioxide from the air into their constituent parts, and then when they are burned, that carbon is released back into the sky. Sisal and sugar production is widespread in East and South Africa, and yet the excess power typically goes to waste.

Phillip explains that even in the case where a power generation piece is added to a sisal or sugar refinery, the operators can’t usually produce electricity unless about 70% of the capacity is used: otherwise the boiler malfunctions. In the case of the sugar refinery, there was no one close enough to buy the power. In the case of the sisal farm, the power generation feature was simply never turned on. Again: enter Bitcoin. With Gridless technology, these power stations are now running at close to full capacity, and saving the previously orphaned electricity, turning it into capital.

“ASICs will become an integrated component of any energy site,” says Philip. “A turbine, a transformer, and a mining container. This is just what you will do. If you don’t, you won’t be competitive. You’ll be wasting energy.”

IV. Bitcoin Without Internet

As of 2023, some 600 million Africans lacked internet access. More than half the continent is still offline. Starlink makes what Gridless does possible, and innovative companies like BRCK continue to expand internet access in rural places. But what good can Bitcoin do for the average citizen of a country like Malawi, where only a fraction of the population is online?

Ten years ago, Bitcoin educator Andreas Antonopolous wondered: what if Africa could leapfrog banks, just like it had leapfrogged landline telephones? What if people just used their phones to access Bitcoin-powered financial services? He even wondered: could this be possible without internet access?

As fate would have it, an entrepreneur named Kgothatso Ngako born in Mamelodi, a township outside of Pretoria originally built by the apartheid government of South Africa, would come up with a solution.

Ngako -- or “KG” as he is commonly known -- was working as a computer scientist at the Council for Science and Industrial Research in Pretoria about 8 years ago when his boss gave him a new assignment: research Bitcoin.

KG was once offered a $1,000 payment in Bitcoin in 2016 for a remote gig (1.3 BTC then, worth more than $50,000 today), but took the payment in PayPal instead. Why? He couldn’t use Bitcoin for anything. The CSIR study he worked on rekindled his interest, but ultimately the researchers concluded that blockchain technology was the thing that had merit, not Bitcoin.

In 2017, Bitcoin’s price shot up and KG, like many others, finally took a harder look. But what initially attracted his interest was the galaxy of crypto tokens that sprouted up around Bitcoin. By early 2018, when the next bear market began to hit, he was trading a dizzying array of tokens on Binance. He had a bunch of altcoins that had lost so much value they couldn’t even be traded on the engine, so KG visited a “dust page” to convert them into Binance’s native BNB token and from there he converted to BTC.

He eventually did enough reading and research and had seen enough: he wanted to start saving in and working in Bitcoin, not other digital currencies. Warren Buffet in particular had inspired him: what will gain value over 30 years, thought KG? Bitcoin, he thought, and maybe not so much the other tokens.

The first Bitcoin project KG created was Exonumia, named after an old word for the study of currencies and numismatics. In 2018, he wasn’t ready to contribute to Bitcoin with code, but at least, he thought, he could introduce the idea to more people. Exonumia is an African-wide translation platform, still in operation today, that puts Bitcoin educational materials into dozens of African languages from Berber to Malagasy to Shona. The key, KG said, was the architecture of the translation itself.

Most people would try to automate translations using software. But that wasn’t the full point of the mission. Building a human network was the real goal. So KG did it the “slow way” and would recruit people from various countries in Africa and pay them to do the work. Over time, he got to know Bitcoiners in dozens of places across the continent. In 2019, he expanded this network by hosting regular spaces on Twitter and inviting anyone in Africa with an interest in Bitcoin. People would message him out of the blue on the Exonumia account, with new ideas, from new countries, and new projects were born.

After his CSIR job, KG took a role at AWS. But ultimately, the work there felt like it was taking him further away from the things he found interesting. It was, as he says, completely disconnected from the realities of life back in the South African townships where he grew up.

Exomunia seemed so much more important. At the end of 2020, he decided to quit the corporate world and work full-time on freedom technology. The first software project that he spun up was a VPN, called ContentConnect.Net. Privacy is hugely important to KG. Not that long ago, he says, South Africans lived under a dictatorial state of surveillance and control. He pointed out that Steve Biko published his famous “I Write What I Like” essays under a pseudonym: once the authorities found out he was the author, they put him on trial and killed him.

Everyone can be a hero, KG says, but if they feel like it’s too risky, they won’t take the biggest steps. So creating a privacy-boosting VPN accessible to Africans was a worthy goal.

KG’s next project was a software solution to what he saw as one of the biggest barriers to Bitcoin adoption in Africa: the lack of internet access. 10 years ago, he was part of an MIT Global Startup Labs effort working on mobile money in South Africa. The problem was that the mobile money system was fragmented, and they wanted to try to bridge the different types of credits that people used across the country. This is where he started tinkering with USSD: a protocol for communication over text messaging, no internet required. In May of 2022, a Namibian Bitcoiner wrote “There has got to be a way to get a Bitcoin wallet onto a non-smartphone mobile phone. Someone out there is definitely smart enough to figure this out. I believe in you.” KG quickly responded: “Give me 2 weeks.” He was ready. He had taken a pay cut (known as a “soul dividend”) when he left Amazon to work on his VPN, but was more energized than ever to work on Bitcoin.

A few days after his famous tweet, with the experience from the MIT challenge a decade ago in mind, he launched Machankura, referring to the South African slang term for money. The new service would allow feature phone users -- or smartphone users with no data -- to send, receive, and save Bitcoin. Some of the biggest challenges that Machankura overcomes are in the UX area: traditionally, to use Bitcoin, people need to copy and paste an address, or read a QR code. But feature phones in general do not have these capabilities. KG’s tool would also need to use Lightning, to overcome the increasingly high on-chain fees, but USSD has a 182 character limit, so lengthy Lightning invoices were not going to fit. The solution was to adopt the Lightning Address, a mechanism invented by the Brazilian software engineers Andre Neves and Fiatjaf, which gives Machankura users an email-based, human-readable identity. For example: [your phone number]@8333.mobi.

Today, Machankura users can send Bitcoin to each other using phone numbers or Lightning Address “usernames.” They can also use on-chain addresses or Lightning invoices, assuming their phones have copy-paste functionality, but the former two options are dominant. To fire up the service, a user dials a number from their phone, generating a text response with various options, a decision-tree of sorts. To send, press 1, etc. From here a user can do a variety of things with Bitcoin with no internet.

One powerful functionality is the overlap with Azteco, a voucher service. So for example, KG might go into a convenience store in South Africa, and with cash buy a voucher called OneVoucher. In Kenya someone might buy a similar voucher using MPESA. It’s a 16-digit code with a certain amount of value on it, and this code can be entered into the Machankura menu. On the back end, what KG and team are doing is buying an Azteco voucher with the 16-digit code, and crediting the account of the Machankura user. This allows Machankura users to easily “top up” their Bitcoin account using cash or MPESA credits.

Machankura also has an API to Bitrefill, so any product available on Bitrefill can be sold on the app’s user interface. Availability ranges by country but when they go to option 4 inside the app, they can barter for goods and services: for example, airtime or grocery vouchers. What this means is today, as we begin the year 2024, Machankura’s user base of 12,000 Africans are able to send and receive value globally, buy mobile minutes, buy vouchers for gas or petrol, purchase electricity (through pre-paid vouchers), or trade into cash, all using Bitcoin, with no internet. KG’s dream is starting to be realized.

Of course, big challenges remain. One is scaling across the entire African continent. Right now, KG works with services like Africas Talking to access different telecom networks. In that model, Machankura pays a monthly fee to Africas Talking for airtime, instead of the users paying the telecom directly. The scaling is a slow but steady process, but is happening, even in places like Malawi. A second challenge is custody. At the moment, Machankura is a custodial service. Meaning: they hold your Bitcoin. Not your keys, not your coins. So even though it’s a very useful tool, it’s not actually giving property rights to its users. But, in the coming month, Machankura is planning to release a proof-of-concept that allows users to self-custody. If it works smoothly, it will be one of the biggest innovations in Bitcoin’s history, allowing people without the internet to actually be their own bank.

The trick, KG says, is that a SIM card is a computational platform that can store things. It can, for example, sign Bitcoin transactions, or interface with the Lightning Network. He is incentivized to push Machankura in this direction for the mission of human freedom, but also, for business reasons: they don’t want to grow as big as MPesa, and be liable for all user funds, and to carry so much counterparty risk. This way, when KG goes to Vodaphone to pitch a partnership for tens of millions of new users, he can say: how would you like to introduce your users to Bitcoin, with no counterparty risk? It’s a much easier “yes” than if he were to say: let’s introduce your users to Bitcoin, but you have to hold all the funds, and deal with those regulations and laws and responsibilities.

In the West, Bitcoin adoption might mean the centralizing forces of large on-grid mining operations and ETFs. But the amazing irony is that in Africa, Bitcoin’s technology arc is making the currency more and more decentralized. As the network eats more and more off-grid cheap electricity, at dozens of completely separated sites, it becomes harder and harder to shut down. And as the network adds more and more self-custodial users on potentially millions and millions of SIM cards, it becomes more and more unstoppable. As Lyn Alden describes in her book, Broken Money, up to this point modern monetary technology was inexorably centralizing as it became more digital and more advanced. Bitcoin breaks this trend, and Africa helps Bitcoin break it.

And as Africa helps Bitcoin, Bitcoin helps Africans. KG says that some Machankura users started with feature phones, and then, after getting involved in the Bitcoin economy, bought themselves a smartphone. They are pulling themselves into the internet using Bitcoin. And others through Gridless are pulling themselves into electricity using Bitcoin. Together, they are moving into the future.

V. Bridging the Gender Gap

There are 700 million African women. All of them, according to Marcel Lorraine, could one day be Bitcoin users. Marcel, a Kenyan entrepreneur and social activist, has made it her life mission to onboard the women of Africa into a new currency system that they (not their husbands) can control, and that can meaningfully improve their own freedom.

Her journey began in 2018, when she was doing a gig in Nairobi and struggling with her finances. She was running Loryce, her company that consults for corporate and social events. She would save her earnings, she says, but then at the end of the year have less and less to show for it. The government, she says, kept raising taxes. And her only option was to save in a shilling bank account, which kept depreciating rapidly. For context, while not as weak as the kwacha, the Kenyan shilling depreciated 21% against the dollar in 2023, which itself also depreciated against goods and services. In the end, Kenyans are getting at least 25% less stuff for their wages than one year ago.

At the gig, Marcel heard about cryptocurrency and decentralized finance. “Can I be paid in that,” she asked herself, “to save me from the hassle of fees and inflation?” At that time, she said, there was a ridiculous amount of hype around blockchain in Kenya. There were tons of scams, and tons of promoted events around different tokens. During that time there were no educational hubs or groups: you’d show up at an event and hope it wasn’t pitching a scam. “I invested in a variety of tokens,” she says, “including Bitcoin. I made money. I lost money. It was frustrating.”

During the COVID pandemic, she couldn’t do event production, so she was day trading shillings and dollars. She decided to focus on Bitcoin, because she didn’t have time to study more than one type of investment, and besides, as she says, it is the mother of digital currencies.

In 2022, Marcel helped organize the first post-pandemic Bitcoin event in Kenya in April at a Nairobi hotel at a conference room full of Bitcoiners. Attendees included local educators Rufas Kamau and Master Guantai, and even Paco de la India, who was passing through on his journey to travel the world only using Bitcoin. At that event Marcel noticed a problem: there were a lot of men but only two women, and she was one of the two. She had noticed that crypto and blockchain events had a gender gap, perhaps only 30% women. But 98-2 for Bitcoin? “We could do better,” she said. So she reached out to a few female friends, who told her that they were afraid to go to Bitcoin events, because the environment felt male dominated. OK fine, she thought: “There’s a problem and I can make a solution.”

Marcel created Bitcoin DADA in 2022 as a safe space for girls and women to learn about financial freedom. The first cohort was held in May, with 20 people, just her circle of friends. Ever since, she has run online classes every Tuesday and Thursday at 9:00pm. At first, it was just Kenyan females. In the second cohort, they had 40 students. Each cohort is 6 weeks long. Now, she says, they have held five cohorts, and more than 300 women have gone through the course, with a total of 130 graduates. All of them now have a solid understanding of Bitcoin. They know how to self-custody and buy Bitcoin with no KYC via cash trades.

On our way through Nairobi, I watch as Marcel effortlessly uses Bitnob and Machankura to buy Bitcoin with MPESA, and then send Bitcoin without using any data. I think of how people on Wall Street or Silicon Valley would be blown away by this feat, which she makes look so simple. Marcel normally suggests a range of wallets in her course, including the self-custodial Muun and Phoenix, and the custodial Wallet of Satoshi for small transactions.

For on ramps, Marcel typically recommends the Nigerian-founded Bitnob app. Students, like everyone in Kenya, have MPESA, and use Bitnob to swap that for Bitcoin and then withdraw to, for example, a Muun wallet. Kenya is much more developed than Malawi, but many smartphone users still don’t have consistent data, rendering Machankura also a key tool. For the main curriculum, Marcel uses the Mi Primer Bitcoin book (originally created in El Salvador) and then she walks students through practical examples of why it’s important for African females to become Bitcoiners.

Back in 2022, Marcel first heard about the Africa Bitcoin Conference. The Austrian educator Anita Posch approached Marcel and asked if she was going: no, Marcel said, it was too expensive. But Anita insisted and helped organize a fundraiser, and contributed half while the community covered the rest. On her visit to Accra in December 2022, Marcel was inspired by what the conference organizer and Togolese human rights activist Farida Nabourema had created. In 2023, Marcel came back to the second edition of the conference with 4 ladies, and Bitcoin DADA helped two female-led teams enter the event’s hackathon. Marcel now offers a mentorship program which helps the ladies speak in their own capacities, whether on social media or at events like ABC, to help them tell their own stories.

On the ground, Marcel visits universities and runs trainings for women and men together. Students are vulnerable because they are often targeted by scams. She describes the obscene lengths that WorldCoin went to try and sucker students into buying and trading their token in Kenya. Bitcoin, she points out, has no similar marketing budget. Teaching and training the youth, she says, is underfunded and vitally important. Every single person that attended one of her events at a university recently had been targeted by WorldCoin: a brutal reality.

Marcel’s goals are to streamline DADA’s mentorship program so that they can match talent and skill for Bitcoin companies, to help get women hired in the space, and also to expand to different countries. Several of her mentees have already earned jobs or fellowships in the Bitcoin ecosystem, at organizations like Btrust or ABC. She says they now have 30 active alumni in Uganda now, and more in Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania.

“For me,” Marcel says, “Bitcoin gives us back our voices. It’s hard being African, and harder being an African female. This gives us financial independence and an opportunity to work on ourselves.”

Marcel has long supported one particular school in Nairobi’s Kibera, the largest urban slum in Africa. She has personally seen Bitcoin help people escape. She knows it can help get many many more, but the hard work needs to be done.

Her mission seems a tall order: going from what is now probably just a few thousand African female Bitcoiners to tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions, and eventually, hundreds of millions. “If I don’t do this,” Marcel says, “then I would have failed my sisters. Finance is thought to be a man’s thing, so women get financially abused. I don’t want to leave the women behind.”

Bitcoin, she says, gives a way out of macro problems like currency devaluation, and micro problems like repression inside the home. A lot of foreign aid, she says, doesn’t make it to the slums. Bitcoin helps because it makes sure the money gets directly where it needs to be: “We eliminate the waste and corruption.”

On my last night in Nairobi, I meet Felix, a local Bitcoin entrepreneur. Like many others I met, he’s now running a Bitcoin business, in his case selling merchandise, and is earning in satoshis. He explains how the Lightning integration at Binance has been huge for Kenyans, as now they can interface with Wallet of Satoshi, Phoenix, Machankura, and other apps instantly with very low fees. He says how Binance p2p is also being used widely to trade from MPESA to Bitcoin. I ask him about Marcel, and he raves about her work. He says that it’s essential to get women involved in Bitcoin adoption, and that Marcel is doing god’s work in this area. “She is,” he said, “bridging the gap.”

VI. African Producers, not Consumers

Bitcoin mining might help provide electricity to millions of Africans, but if the proceeds aren’t spendable in a local economy, and usable by all citizens, then it’s just a partial revolution. If one challenge for popular Bitcoin adoption in Africa is the lack of internet, and another is low use among women, then another, according to Femi Longe, is breaking the cycle of dependence on the West.

Femi is a Nigerian social entrepreneur with 20 years of experience mentoring African technologists and start-up founders, and played a key role in creating and running the two most important tech hubs in Nigeria and Kenya. In 2022 he was hired to lead the Qala Fellows, an initiative from Tim Akinbo, Carla Kirk-Cohen, Bernard Parah, and Abubakar Nur Khalil to accelerate the process of moving African computer engineers into contributing to the Bitcoin ecosystem.

Last year, Qala was acquired by Btrust -- the charity founded by Jack Dorsey and Jay-Z to support Bitcoin infrastructure in Africa and the Global South -- and renamed Btrust Builders, where Femi now sits as director. He is focused on helping Africans move up the value chain in Bitcoin. Rather than just being consumers, like Africans are in so many ways in the existing global financial system, he wants them to be producers in the new Bitcoin economy.

Femi says there are two legs to this journey: first, getting Africans more involved in protocol and infrastructure discussions. As Jack Dorsey says, if Bitcoin is going to be money for the world, it has to be made around the world. Femi says that African views will be needed to help evolve Bitcoin to its true potential. We can already see evidence of that in Machankura’s product road map, which could help decentralize and strengthen Bitcoin by creating potentially millions of more self-custodial users, and Gridless’s work, which makes mining more censorship-resistant and robust. The second leg to the journey, Femi says, is creating Bitcoin tools and applications that help Africans improve their quality of life, in the context of their own community, city, and country.

Femi says that these are early days: in 2022, when Qala participated in a hackathon around the first Africa Bitcoin Conference, they struggled to attract participants. People were “just dipping their feet in,” said Femi. But in 2023, he said the influx of talent was impressive. One winner was BitPension, a start-up aiming to allow anyone in Africa to set up a BTC-denominated pension, where anyone can buy satoshis in small amounts every day, which go into a time-locked self-custody, so that you can’t betray yourself. Today’s pensions, Femi says, could easily rug you, or they could be investing in oil or weapons companies. BitPension, or a similar idea, could be game-changing. The company won $5,000 of BTC, and is currently building a minimum viable product. Femi also pointed out Splice, another hackathon entrant, which is leveraging local communities of mobile money agents to facilitate dollar-stabilized trades over Lightning using Taproot Assets.

Femi says that the Western mentality around Bitcoin is too focused on the savings aspect, and not enough on the medium of exchange part. In his view, this overemphasis on savings slows down the adoption, and cements fiat currency as the on-ramp to Bitcoin. A lot of the work that needs to be done is not just teaching people how to save, but also sitting down with local rideshare apps, for example, and showing them how they can add native Bitcoin payments. The only way we can get out of the broken currency system is to build a new one, he says, to leave the old one entirely behind.

Consider the average person’s day, says Femi, and ask: what are all the touch points where they are going to interact with money? Now: how do we put Bitcoin at any one of them? How do we help create options for them to spend the Bitcoin that they earn? If they don’t have those options, Femi says, they remain part of the exploitative fiat system. The more merchant services we have, he believes, the more goods we can buy, and the less interest there will be in the conversion to USD aspect. “If we don’t get merchant traction,” he says, “we are stuck in the past.”

Another insight Femi has is that wallets will be in the future features, not core products. “Where you keep your coins is important. More important is what you can do with them,” he says. There will be, he says, pension solutions, international trade settlement solutions, payroll solutions: currently, a lot of these services are disconnected from wallets, eventually those will be built in.

Something else Femi is focused on is helping Africans build strong narratives. He points to the fact th

You can get bonuses upto $100 FREE BONUS when you:

💰 Install these recommended apps:

💲 SocialGood - 100% Crypto Back on Everyday Shopping

💲 xPortal - The DeFi For The Next Billion

💲 CryptoTab Browser - Lightweight, fast, and ready to mine!

💰 Register on these recommended exchanges:

🟡 Binance🟡 Bitfinex🟡 Bitmart🟡 Bittrex🟡 Bitget

🟡 CoinEx🟡 Crypto.com🟡 Gate.io🟡 Huobi🟡 Kucoin.

Comments